Using clangd for PostgreSQL development

I have started using clangd (with a “d”) for PostgreSQL development. Maybe you want to try it too.

Introduction

What is clangd? To quote directly from the web site:

clangd understands your C++ code and adds smart features to your editor: code completion, compile errors, go-to-definition and more.

clangd is a language server that can work with many editors via a plugin.

(They talk about C++, but this applies to C equally.)

Of course, editors can already do this. But previous solutions usually involved a hodgepodge of third-party tools that analyze source files with varying amounts of awareness about what the source code means. The classics are ctags and etags, many people like to use GLIMPSE, I have written about GNU Global before. By contrast, clangd is based on an actual compiler tool chain, so clangd understands your code exactly like a compiler would.

I’m going to describe using Emacs and clangd. If you are using Emacs as well, you can follow along directly. If not, maybe you can use this as inspiration to set it up for your editor, and then share the experience. See also the clangd documentation for editor integration.

The quote above describes clangd as a “language server”. This refers to the Language Server Protocol (LSP). Let’s quote from their web site now:

The Language Server Protocol (LSP) defines the protocol used between an editor or IDE and a language server that provides language features like auto complete, go to definition, find all references etc.

Sounds good!

To be clear, the LSP isn’t technically necessary to achieve this. This kind of thing was certainly possible earlier. But the setup was usually more complicated, and each combination of editor and language had to be created and maintained and configured separately. The LSP has allowed this ecosystem to arise where different editors and different languages can communicate with each other through a common interface.

Also, these language “servers” are servers in the sense that they provide a service, but they are not (necessarily) long-running processes. They are processes called by the editor (the client) as necessary, they are not started separately.

Setup

Now let’s look at the actual setup. What you need:

-

GNU Emacs version 29 (released in July 2023). This version includes LSP support by default. The package that provides LSP support for Emacs is called Eglot; it’s also available for older Emacs versions as a separately installable package. But let’s go with the one where it’s built in.

-

clangd. This is part of LLVM and should be available from your package manager. (For example, on Ubuntu, it’s in a package called

clangd.)(When using clangd to support your editor, you don’t necessarily need to use clang for the actual compilation of the project, but it could help; see below.)

-

You need to use Meson for building PostgreSQL. The reason for that is as follows. clangd needs to know how to compile each source file, to be able to show warnings etc. By default, it will assume

clang filename.c, but that usually won’t work because it won’t know about all the include paths, warning options, and other compiler options. This is where previous, more simplistic editor integrations usually failed to the point of uselessness. The solution is that Meson produces a filecompile_commands.jsonthat records the compile command for each source file. This is also called a compilation database. This is another standard that different build systems know about. For PostgreSQL, you only get that if using Meson. (Actually, you don’t need to use Meson for building PostgreSQL. You just need to runmeson setupto create the compilation database.) -

The default configuration of clangd assumes the build directory is called “build”. So it’s sensible to stick with that, but you can configure things differently if you want to.

-

One possible source of trouble is: Since

compile_commands.jsonis used by clangd, the commands need to be understandable by the clang/LLVM universe. If you use a different compiler, then the commands might contain options that clang doesn’t understand, and then the whole thing will fail. So at least to get started, I recommend building with clang, and better even with the clang version that matches the clangd version. When that works, then you can branch out and try other combinations. (In theory, the GCC project could also provide a language server that is based on the GCC backend, which would address this issue from their end, but that doesn’t exist at the moment.)1

Now let’s open a file in Emacs with the default configuration (just to show that it works out of the box — of course you can keep using your existing configuration):

emacs -Q src/backend/commands/tablecmds.c

Eglot isn’t enabled by default, so manually enable it for the buffer:

M-x eglot

On the first run, this will do some indexing work, which could take

about a minute. The indexing work is cached in .cache/clangd/ under

the top-level directory of the source tree. (Maybe have Git ignore

that somehow?) Note that this indexes the whole project, not just one

file. (Emacs is aware of what set of files constitutes a “project”

based on where the .git/ directory is. See also the

documentation.)

If you like using this, then of course you will want to have it activate automatically. See the Eglot documentation and the clangd documentation for some ways to do this.

Using

Now what can you do with this? Let’s look at some pictures.

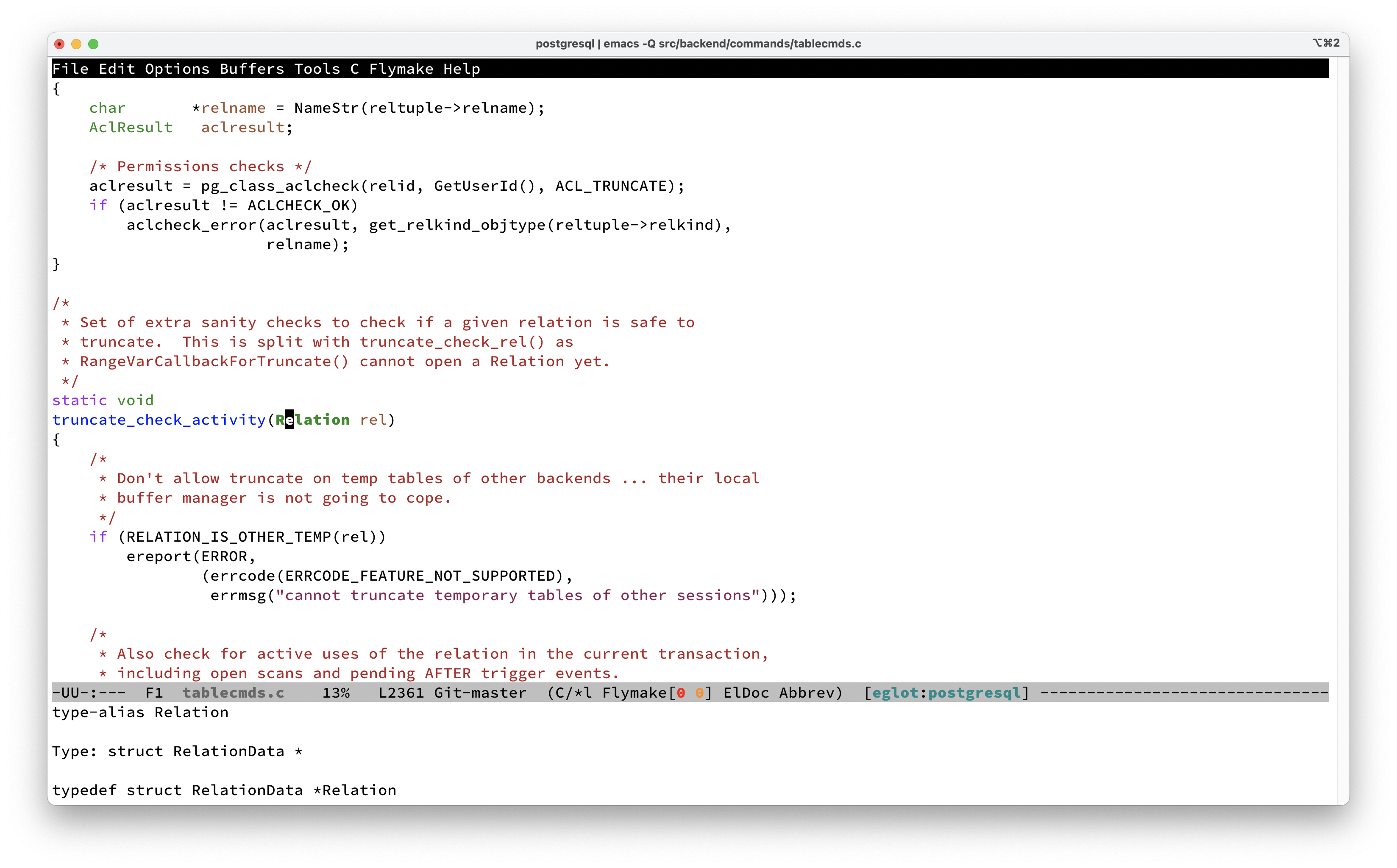

Just parking the cursor on a symbol shows you the definition of the symbol:

See how it also shows the documentation comment for the symbol. This doesn’t require any special formatting for the comment, as far as I can tell.

You can jump to the definition of a symbol using M-. as usual.

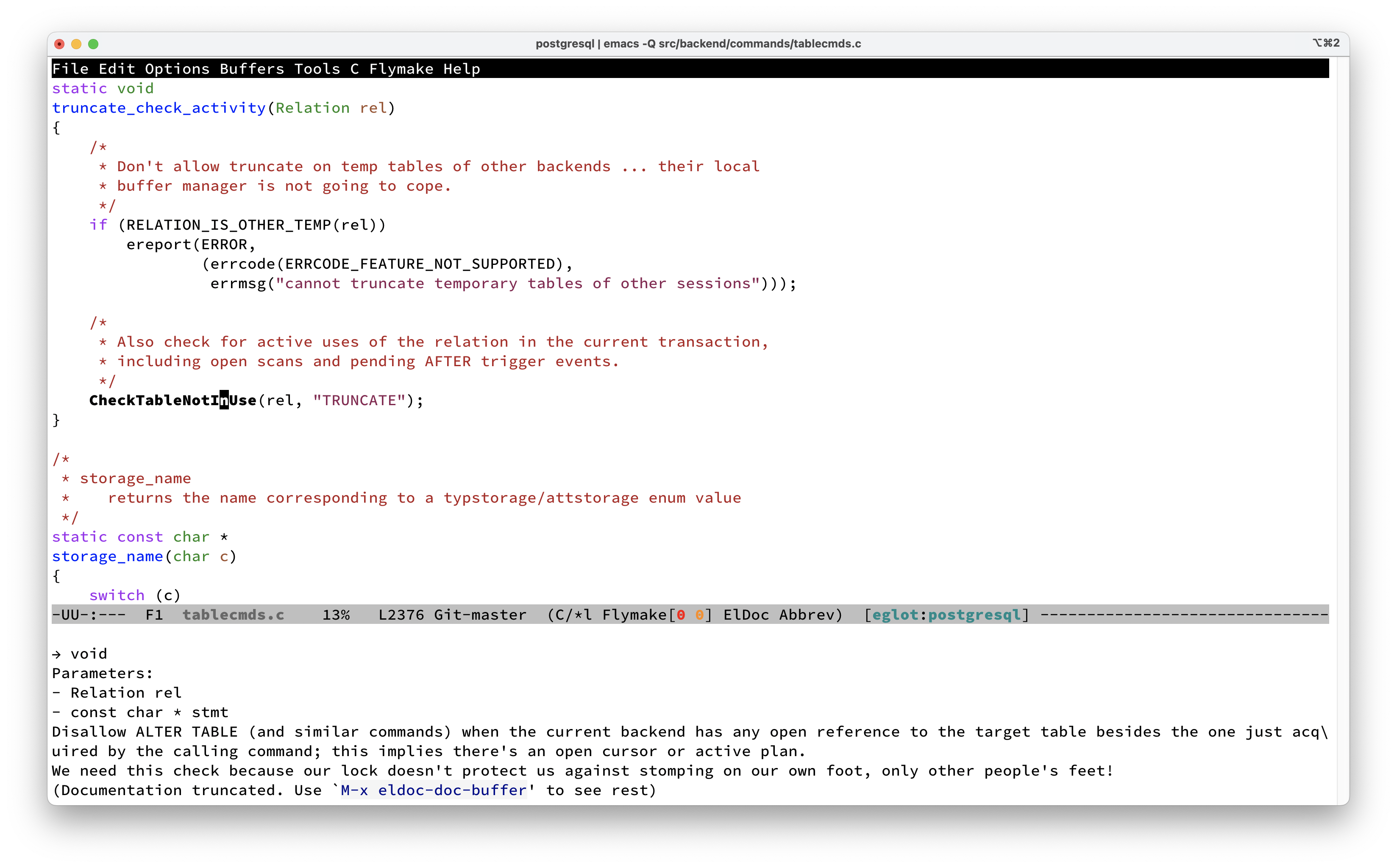

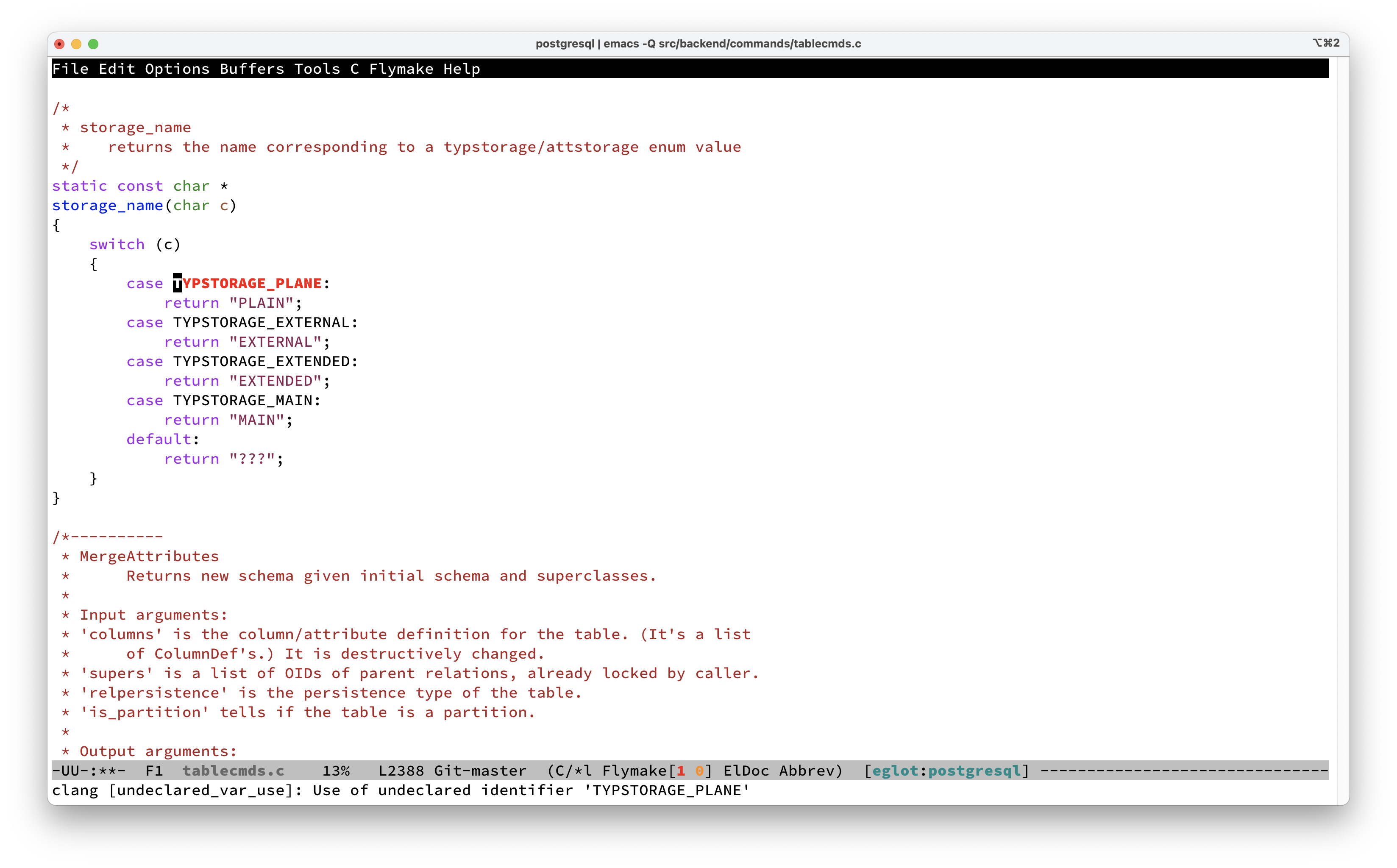

Compilation of the file is done continuously in the background as it is edited, and errors are highlighted:

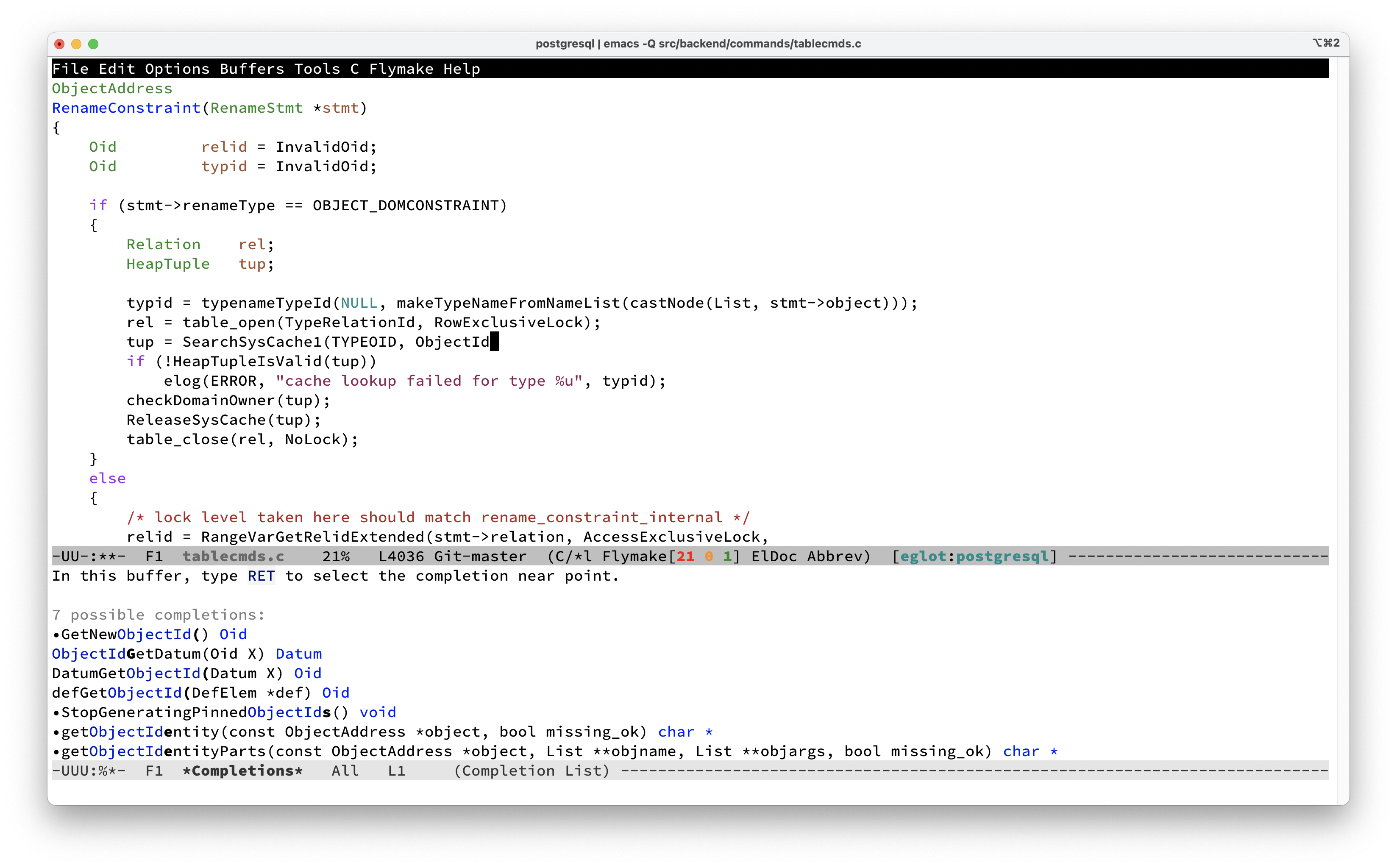

M-x completion-at-point works, of course:

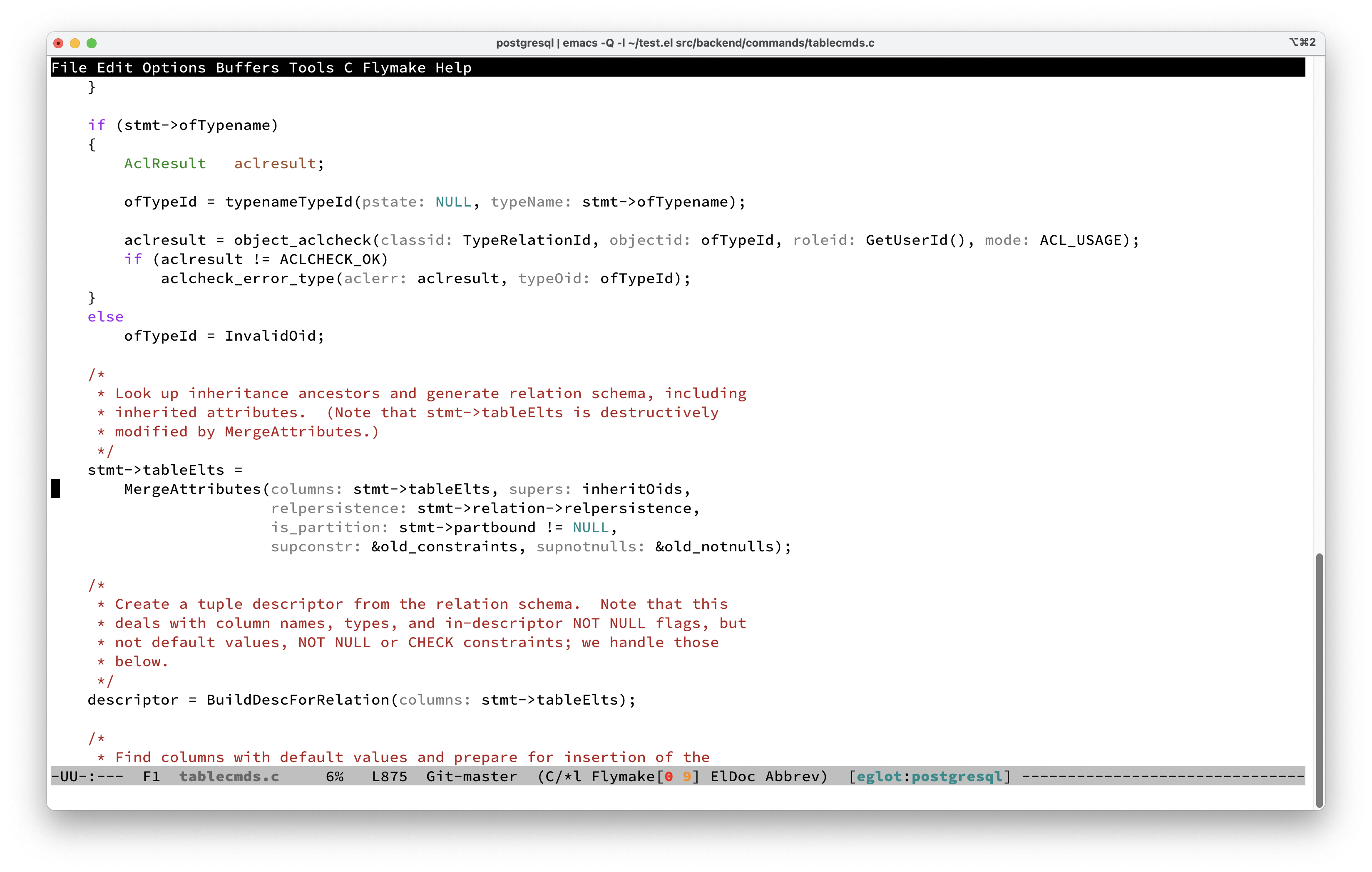

Some features may only be available with newer clangd versions. Consider this demonry, which required a newer version than was standard on my system:

Do you see it? These are called inlay

hints,

a perfect feature to either love or hate! (Toggle with M-x

eglot-inlay-hints-mode.)

Some functionality doesn’t quite work (yet?). For example,

eglot-rename will indeed correctly rename symbols across the source

tree, but it will not update any mentions in comments. eglot-format

doesn’t work for PostgreSQL, because it relies on clang-tidy. But

it’s probably a good option for smaller projects with simpler

formatting requirements. Also, when editing header files in the

PostgreSQL source tree, the syntax checking doesn’t work right,

because the header files are not in the compilation database. All of

this is very configurable and still evolving, so some of these issues

might get solved in the future or already have workarounds.

Summary

So, this seems a lot better than previous solutions to make editors aware of source code semantics. With Meson providing the compilation database, this is ready to go. And it works pretty much out of the box.

Thanks to fellow PostgreSQL contributor Peter Geoghegan for suggesting that I try out clangd.

-

Update 2024-04-09: I might have misinterpreted the problem I had at the time. I was using gcc for the compiler and was getting lots of errors from clangd, and I thought this was because of the different command-line options. clangd actually has some smarts to handle options from other compiler families. The problem I had was caused (or at least surfaced) by the

-Werroroption, activated bymeson setup -Dwerror=true(which I always use and generally recommend for development). My workaround for now is a global clangd configuration file containingCompileFlags: Remove: -WerrorSince there is no point in making warnings fatal in an editor, I think this workaround is generally applicable. ↩